“When we are deeply connected to people, we are much less likely to cause harm,” said Rachel Cox, Clinical Director of Community Against Violence (CAV), of their framework for preventing violence on individual, community, and structural levels. CAV has been serving North Central New Mexico in domestic violence and sexual assault services and programs for 42 years. Seven years ago, the organization went through a radical transformation as they considered how their organizational structure could create more equitable power dynamics. This is their story of shifting their practice of supervision and eliminating the rules of their shelter.

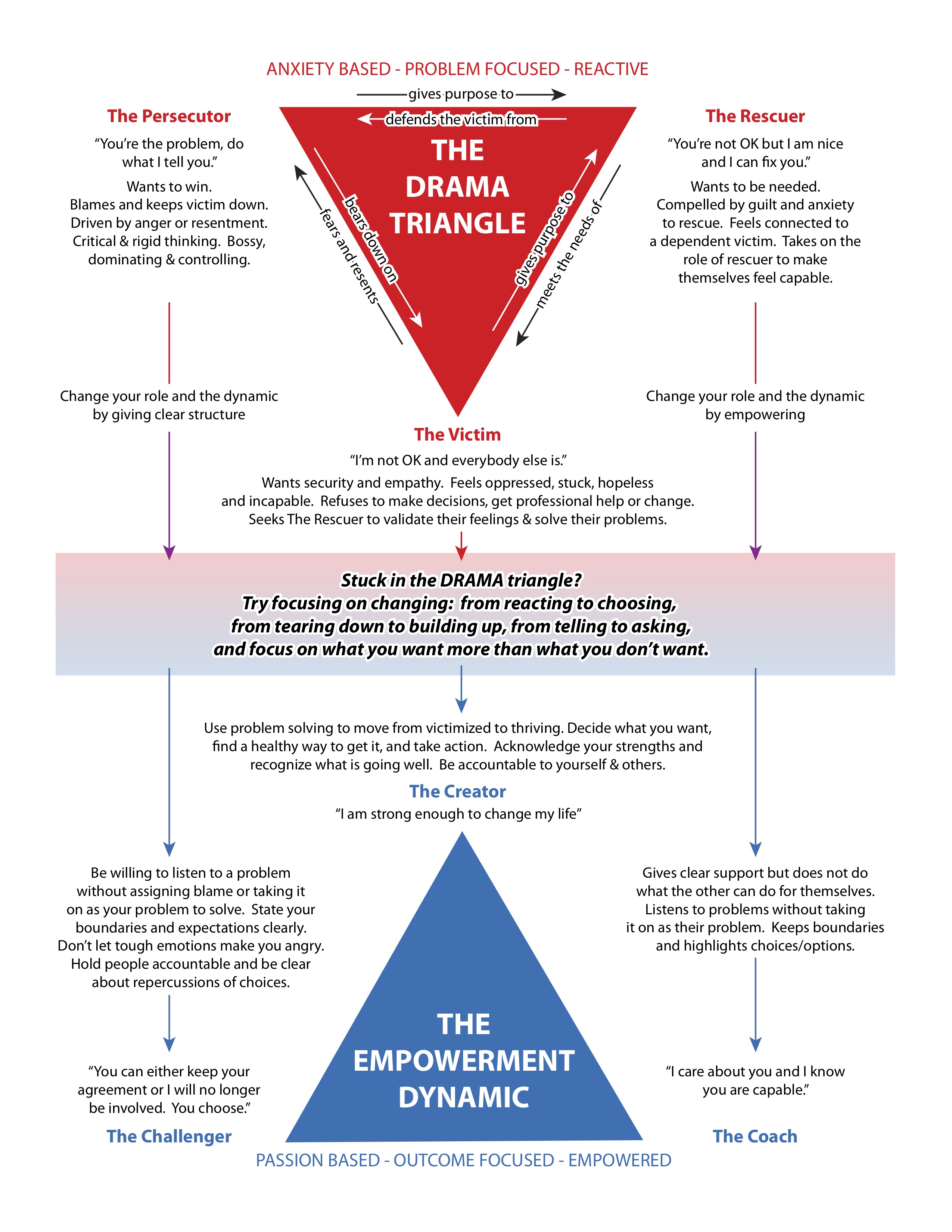

The first changes were made in the prevention program and the shelter program. In domestic violence agencies, clients are sometimes exposed to the Karpman drama triangle (see image below), which outlines an unhealthy dynamic that can play out in relationships between individuals. Those at CAV saw some elements of this dynamic play out in the way the agency related to clients and how supervisors related to staff, and as a result they took steps to create systems that promoted “coaching” rather than “rescuing.”

The roles outlined by Karpmann–the persecutor, the rescuer, the victim, the challenger, the coach, and the victim are not fixed and sometimes a person will shift from one role to another within a relationship. In the diagram, the red triangle constitutes the unhealthy dynamic that casts the victim as helpless and needing saving by the rescuer. The person taking on the rescuer role reinforces the belief that the victim must be saved by stepping in and acting on their behalf, whereas the person taking on the role of the persecutor blames the victim for problems, acts out of anger, and does not take responsibility for their role in conflict. This dynamic, by its nature, creates a spiral of hurt feelings and unresolved conflicts. In order to escape the drama triangle, Karpman suggests shifting the roles and goals of each player in the triangle to escape the drama triangle. In the blue triangle, the victim is now not only the creator, but also at the top of the triangle, having the most agency. The creator is empowered to solve problems and take ownership of their life and decisions. The rescuer becomes the coach, who believes in the creator’s power to transform their life and offers support without making decisions for them. The persecutor becomes the challenger, listening to the creator without blame or judgement. The challenger sets clear boundaries for themself. Additionally, they can effectively shift their role to that of the challenger by taking responsibility for understanding their feelings and not acting out of anger.

When in the advocacy and therapeutic role, CAV staff found themselves taking on the role of the rescuer. They decided to move the organizational structure to be more aligned with their anti-oppression values and better support healing. After adopting an agency-wide approach to supervision called ‘reflective supervision,’ supervisors began meeting with their staff one-on-one using reflective listening and practices. Staff now have regular and consistent times to check-in, reflect and talk not only about how their work is impacting them, but also how they are impacting the people they are working with. This approach, they found, enhances staff’s comfort level in sharing and processing their work, and has contributed to leveling power imbalances between staff and supervisors.

“What happens when you stop trying to control people?” Cox asked. “Violence is a symptom of root causes not addressed. Oppression and power are ultimately a soulful and spiritual disconnect.”

CAV also focused their efforts on strengthening relationships, such as in in the counseling department when staff implemented experiential trips such as outdoor activities, attending community events, and promoting peer supports with clients. Additionally, CAV began a rules reduction process for the shelter. Now, there are no mandatory services, nor is there a curfew.

In line with their new coach role, CAV strives to be more supportive of healing and does not contribute to an unhealthy dynamic between survivor and agency. They found that therapeutic interactions created connection and solved conflicts. According to Cox, “This shift was profoundly transformative for the staff. Many of us come to this work with the expectation that we will be in the business of saving lives. This process allowed us to reflect on that idea of being equally as harmful as the perpetrator–that, in our saving, although well-intended, we were still reinforcing the role of the victim. The reflective process helped us to shift our work from saving to coaching, and, while this was challenging, it ultimately transformed the staff and organization.”

Since this shift, CAV has worked with Ruby’s Place in San Francisco, a similar organization offering shelter and services to people who have experienced domestic violence. CAV shared how to implement structural changes to strengthen relationships and level power imbalances. CAV is continuing this effort with DreamTree, a local Taos youth shelter, to transform their organization to be more conducive to creators rather than victims.

“Interpersonal violence is micro-level system of a macro-level problem.” Cox explains.

In the end, CAV’s goal is to increase connectivity. Their outreach has been to follow the connections. They ask, “where does the organization already have relationships to people in the community? Who in the community is connected to the staff and volunteers? How can those relationships be strengthened and expanded for violence prevention work? What is the path of least resistance? Where do the connections already exist?” Their tactics are not persuasive, but rather process-oriented and organic, focusing on relationship building on a structural level, community level, and an interpersonal level. Why? Because they are all connected, and when we are deeply connected to people, we are much less likely to cause harm.

Recent Comments